A Comparative Study of Generators and Alternators

The terms generator and alternator are frequently used interchangeably, leading to a certain degree of ambiguity. Although both devices transform mechanical energy into electrical energy, they exhibit fundamental differences in their design, operation, and applications. This comprehensive exploration will delve into the complexities of generators and alternators, highlighting their similarities, distinguishing their key attributes, and assessing their suitability for various applications.

I. Core Concepts of Electromechanical Energy Conversion

At the heart of both generators and alternators lies the principle of electromagnetic induction, a discovery attributed to Michael Faraday. This principle posits that a fluctuating magnetic field induces an electromotive force (EMF) in a conductor. This EMF propels the flow of electric current, thereby converting mechanical energy (used to generate the fluctuating magnetic field) into electrical energy. The distinction lies in the application of this principle:

- Generators: Traditionally, generators employ a commutator and brushes to convert the alternating current (AC) produced by the rotating armature into direct current (DC). The commutator, a segmented ring, reverses the current direction at precise intervals, ensuring a unidirectional flow of DC electricity. This mechanism inherently restricts their efficiency and introduces mechanical wear and tear.

- Alternators: In contrast, alternators directly generate alternating current (AC). They utilize slip rings instead of a commutator, allowing the AC produced in the rotating armature to flow directly to the output without any rectification. This streamlined design contributes to higher efficiency and lower maintenance requirements.

II. In-Depth Comparison: Generators vs. Alternators

The following table encapsulates the key distinctions between generators and alternators:

| Feature | Generator (DC) | Alternator (AC) |

|---|---|---|

| Output | Direct Current (DC) | Alternating Current (AC) |

| Construction | Commutator, brushes, armature | Slip rings, stator, rotor |

| Efficiency | Lower (due to commutator losses) | Higher (simpler design) |

| Maintenance | Higher (commutator wear and tear) | Lower |

| Voltage Regulation | More complex, often requires external regulators | Simpler, often built-in regulation |

| Power Output | Typically lower for a given size | Typically higher for a given size |

| Applications | Low-power applications, battery charging, small motors | High-power applications, automotive systems, power grids |

| Cost | Generally lower initial cost | Generally higher initial cost |

| Weight | Can be lighter for low power applications | Can be heavier for high power applications |

III. Detailed Examination of Generator Components and Operation:

A DC generator typically comprises the following components:

- Armature: The rotating part containing coils of wire where the EMF is induced.

- Field Magnet: Generates the magnetic field that interacts with the armature coils. This can be either permanent magnets (for smaller generators) or electromagnets (for larger generators).

- Commutator: A segmented cylindrical conductor that reverses the direction of the current produced in the armature coils, converting AC to DC.

- Brushes: Carbon blocks that make contact with the commutator, allowing current to flow to the external circuit.

The process involves rotating the armature within the magnetic field. The changing magnetic flux through the armature coils induces an alternating EMF. The commutator and brushes then rectify this AC into DC. The voltage generated is directly proportional to the speed of rotation and the strength of the magnetic field. Different types of DC generators exist, including shunt-wound, series-wound, and compound-wound generators, each with specific voltage-current characteristics.

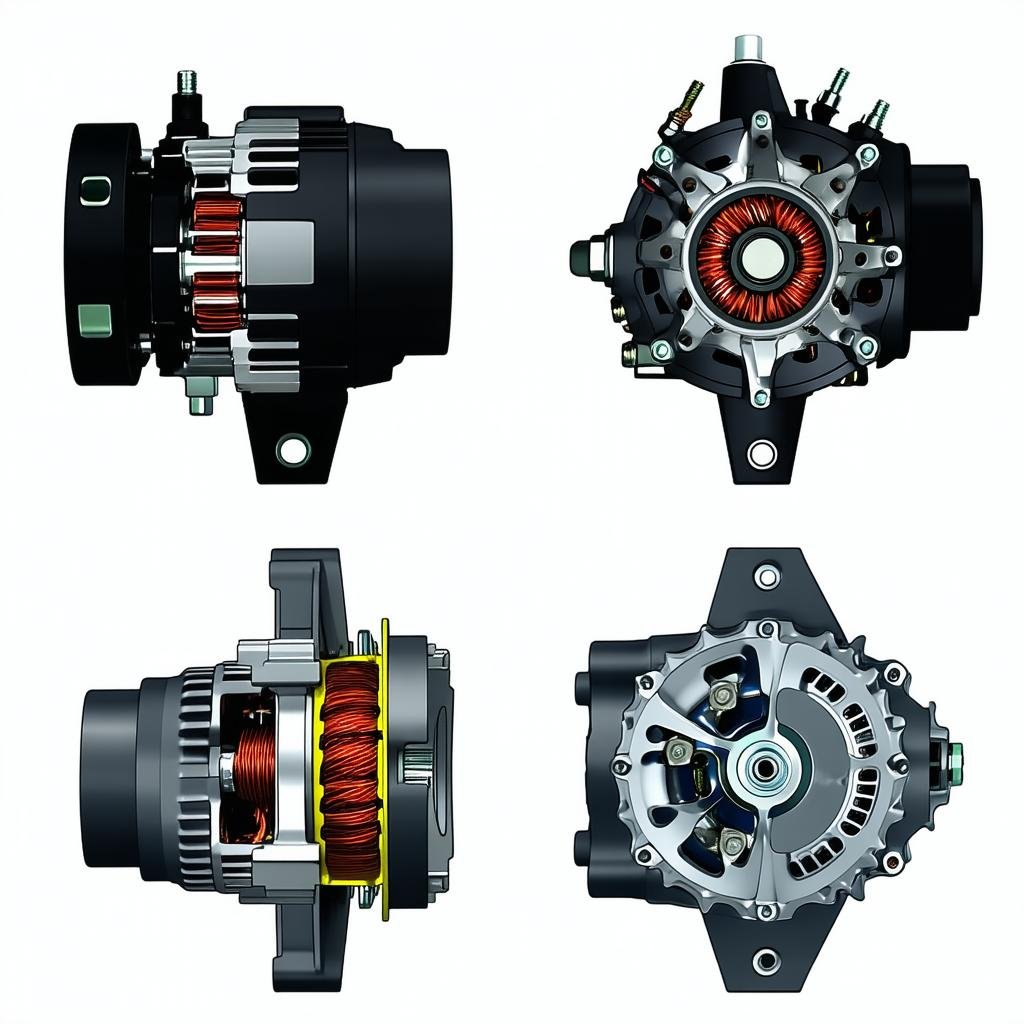

IV. Detailed Examination of Alternator Components and Operation:

An alternator typically consists of the following components:

- Stator: The stationary part containing the coils of wire where the EMF is induced. The stator windings are arranged in a specific pattern to produce a three-phase AC output in most applications.

- Rotor: The rotating part that generates the magnetic field. This usually consists of electromagnets excited by a DC current supplied through slip rings.

- Slip Rings: Conductive rings that allow the DC excitation current to reach the rotor.

- Rectifier (optional): In some applications, a rectifier might be added to convert the AC output to DC. However, this is less common than converting AC to DC using external rectifiers.

The operation involves rotating the rotor, generating a rotating magnetic field. This rotating field induces an alternating EMF in the stator windings. The frequency of the AC output is directly proportional to the speed of rotation, while the voltage is proportional to both the speed and the strength of the magnetic field. Three-phase alternators are commonly used in high-power applications due to their efficiency and ability to deliver a more consistent power output. Single-phase alternators are simpler and often used in smaller applications.

V. Voltage Regulation and Excitation Systems:

Both generators and alternators require voltage regulation to maintain a stable output voltage despite changes in load or speed.

- DC Generators: Voltage regulation in DC generators can be achieved through various methods, including using shunt field windings, series field windings, or a combination of both. External voltage regulators are also often employed.

- Alternators: Voltage regulation in alternators is typically achieved by controlling the DC excitation current supplied to the rotor. This is often accomplished using an automatic voltage regulator (AVR), which constantly monitors the output voltage and adjusts the excitation current accordingly. Modern AVRs incorporate sophisticated control algorithms to maintain precise voltage regulation under varying load conditions.

VI. Efficiency and Losses:

While both generators and alternators experience losses, the nature and magnitude of these losses differ:

- Generators: Significant losses arise from the commutator and brushes. These include frictional losses, contact resistance losses, and arcing losses. These losses lead to lower overall efficiency compared to alternators.

- Alternators: Losses in alternators are primarily due to copper losses in the windings, iron losses in the core, and mechanical losses in the bearings. The absence of a commutator results in significantly lower losses and higher efficiency.

VII. Applications and Suitability:

The choice between a generator and an alternator heavily depends on the specific application requirements:

- DC Generators: DC generators find applications in situations requiring a relatively small amount of DC power, such as battery charging, small DC motors, and certain specialized industrial applications. Their simplicity and lower initial cost can be advantageous in such cases.

- Alternators: Alternators are preferred for most high-power applications. Their higher efficiency, lower maintenance, and inherent ability to generate AC power make them ideal for automotive systems, power generation plants, and large-scale industrial applications. The widespread availability of AC motors and other AC-powered equipment further solidifies the dominance of alternators.

VIII. Advancements and Future Trends:

Significant advancements have been made in both generator and alternator technologies. These include the use of advanced materials, improved designs for reducing losses, and the incorporation of sophisticated control systems.

- High-temperature superconductors: Research into high-temperature superconductors holds the promise of significantly improving the efficiency of both generators and alternators by minimizing resistance losses.

- Permanent magnet generators/alternators: The increasing availability of high-strength permanent magnets is leading to the development of more compact and efficient generators and alternators, particularly in smaller applications.

- Power electronics: Advances in power electronics are facilitating the seamless conversion between AC and DC, blurring the lines between the traditional applications of generators and alternators. This opens up possibilities for using alternators in applications that previously favored DC generators and vice-versa.

IX. Case Studies: Specific Applications

Let’s consider some specific applications to illustrate the choice between generators and alternators:

- Automotive applications: Automotive systems overwhelmingly utilize alternators due to their ability to efficiently generate the AC power needed to charge the battery and power various electrical components. The higher efficiency directly translates to better fuel economy.

- Small-scale wind turbines: Smaller wind turbines may utilize DC generators, particularly those directly charging batteries. Larger wind turbines almost exclusively employ alternators connected to the grid through inverters.

- Power plants: Large power plants invariably use alternators to generate the massive amounts of AC power needed to supply electricity to homes and industries. The high efficiency and capacity of alternators are crucial in these applications.

X. Conclusion:

While both generators and alternators achieve the same fundamental goal – converting mechanical energy into electrical energy – their underlying designs and operational characteristics differ significantly. DC generators, with their commutator and brushes, are simpler and often less expensive for low-power applications requiring DC output. However, alternators, with their superior efficiency, lower maintenance, and inherent AC output, dominate high-power applications across diverse sectors. The choice between a generator and an alternator is a critical engineering decision based on the specific needs of the application, considering factors such as power requirements, voltage type, efficiency demands, maintenance costs, and overall system design. Future advancements in materials science and power electronics will continue to shape the landscape of power generation, potentially further blurring the lines between these two fundamental electromechanical devices. However, the core principles of electromagnetic induction remain the foundation upon which both generators and alternators will continue to evolve.